Simon Critchley is a professor of Philosophy at the New School for Social Research in New York. A scholar of continental philosophy and phenomenology, he has played a central role in the anglophone reception of thinkers such as Emmanuel Levinas, Jacques Derrida and Martin Heidegger. Critchley has been engaging in experimental writing, including an acclaimed semi-autobiographical story, Memory Theatre (2014), as well as a leading role in the avant-garde network International Necronautical Society. His philosophical work has traversed a variety of interests in areas such as music, comedy, poetry, and football, ranging anywhere from Greek Tragedy to David Bowie, Samuel Beckett, and Liverpool FC. Simon Critchley has been trying to make philosophy an accessible part of contemporary culture – for instance, through ‘The Stone’, an opinion series that he moderated for the New York Times, attracting millions of readers, and through regular contributions to The Guardian and high-profile public debates –, leading many to rank him as one of the most influential philosophers working today. The author of almost thirty books, some of them – such as Very Little… Almost Nothing (1997), Infinitely Demanding (2007), The Faith of the Faithless (2012), Notes on Suicide (2015), or What We Think About When We Think About Soccer (2017) – have sparked an intense intellectual debate. Simon Critchley has talked to Electra about the route from playing in punk bands in the 1970s to studying philosophy in a French university, the importance of tragedy and football, political disappointments and the need for a public philosophy.

Simon Critchley, one of the most prolific and popular philosophers of the last decades, talks to Electra about some of the varied topics that have been guiding his work, from the role of philosophy in contemporary society to the disillusionment with liberal democracy, the cultural importance of football, and the challenges of autobiographical writing.

René Magritte, Les vacances de Hegel [Hegel’s Holiday], 1958 © Photo: Scala, Florence / Christie’s Images, London

AFONSO DIAS RAMOS What made you study philosophy initially? And how did you end up trying to overcome metaphysics in southern France?

SIMON CRITCHLEY Teachers. That’s the answer. I had a misspent youth and left school at 16, having failed everything apart from geography. I worked in factories and also in swimming pools. I was a songwriter, and it was only a matter of time before my band was going to become hugely successful. But that didn’t happen. I became frustrated. Then I had a very bad industrial accident when I was 18. It reset things for me. I went back to school to do my O and A Levels [General Certificate of Secondary Education − Ordinary and Advanced Levels], and began to really read at that time. I went to university when I was 22. It is always a good idea to be slightly older at university. I did English and European literature. I had become fascinated with James Joyce and other writers. When I arrived at the University of Essex, I studied philosophy in my first year and was incredibly impressed by the teachers, including Jay Bernstein, who is still my colleague. Philosophy gave the freedom to think the way I wanted to. I did philosophy but did it my way, mixing it with other things, and reading the books I wanted to read. Since a lot of those books were in French, I started to entertain the idea of taking the money I was going to get to do a PhD and disappearing into France to live there. My plan was simple: to take the money and run. Then I found myself in Nice. It was not a fashionable university, but I met good teachers such as my mentor Dominique Janicaud, and most famously, Clément Rosset. I learned to do research and to use a library in France. I also had to write in a foreign language, which is very good to clarify your thoughts. Philosophy is a subject you can read for yourself, but it does help to have teachers.

ADR Your first book, The Ethics of Deconstruction (1992), came out as Derrida was denied an honorary degree at Cambridge. What was that experience like? And isn’t the misconception of deconstruction of a value-free nihilism making a comeback today?

SC Very much so. We have had to endure this caricature that always seems to be linked to Derrida as well as Foucault, as if they led to cultural relativism. Idiots like Jordan Peterson will make that argument, but it is not even worth refuting because it is just so wrong. However, the fact that it still exists as a stereotype is interesting. The other thing, which Derrida himself also realized, is that the term deconstruction which he had simply introduced as a translation of words from Heidegger, then acquired this fate of extraordinary generalization and misunderstanding. Even in the Qatar World Cup there were references to the deconstruction of teams! Certain words have a fate way beyond their meaning. In my case, maybe there was something in the air that I picked up. In 1986, I began to work on a PhD on Levinas and Derrida, because not much had been written on either of them. I intuited an ethical dimension in Derrida’s work that was linked to his understanding of Levinas, which had not been articulated. Some time passed, and then an independent publisher agreed to publish what became The Ethics of Deconstruction. It came out around the time of the Cambridge Affair with Derrida. By luck, it became frontline news. One of the headlines in The Independent newspaper said ‘Cognitive Nihilism Hits English City’. And then my book appeared, arguing that there was an ethical dimension to this. The timing helped a lot. It is enormously gratifying to see that the book is still around. But the prejudice about Derrida’s work continues today and I see no sign of it stopping. If it meant that people would actually read Derrida’s work more closely, that would be nice. It is not the case. Henri Bergson was also the most famous philosopher in the world, and was quickly forgotten by the ensuing generation. It wasn’t until Deleuze’s work on Bergson that he came back into the discussion. Derrida has been like that. He was a hugely influential philosopher, with an almost apostolic atmosphere around his work, with disciples and followers... However, his work requires an intense reading of primary texts, and that is not the world we live in. We live in a world of Wikipedia definitions. So even though great things are still being published, I’m not sure what Derrida’s legacy is going to be.

ADR When you wrote Infinitely Demanding (2007), you still worked with insights from Levinas, but the references to Derrida were now reduced to a single footnote.

SC That was deliberate. In the late 1990s, I was trying to recover from Derrida’s work. The invention of the computer was very bad for him. He wrote with enormous fluency on a typewriter, but when he got a computer, he wrote even more! The question was: what is Derrida’s key work? You can answer that in twenty different ways. That is not the case with Foucault, who only has five or six major works, and you can emphasize one over the other. With Derrida, there is too much. In the late 1990s, I was also trying to respond to the battle in Seattle, the beginnings of the anti-globalization movement, and a new radicalization on the left. It made me want a greater economy of thoughts and expression. Infinitely Demanding was the attempt to write a short book that laid out my position on these matters as precisely as possible, with great conceptual clarity. Derrida became less important, and Alain Badiou, from whom I learned the economy of expression and the precision of utterance, became more important. Infinitely Demanding was also an attempt to make an intervention into a political context, moving through the Occupy Movement and Tahrir Square, and Derrida was not included in that argument. He was really a complicated figure. I was close to him, not a follower. He had a strange relation to criticism. In the Ethics of Deconstruction, I included a strong critique of his work on politics, judgment and decision. He didn’t like that, and we fell out. The relationship recovered, but he was very Schmittian, you were either a friend or an enemy. But of course, that is not what Derrida’s work is about. It is about exploring ambiguities and hesitations in texts, about showing how texts are largely written against themselves.

[...]

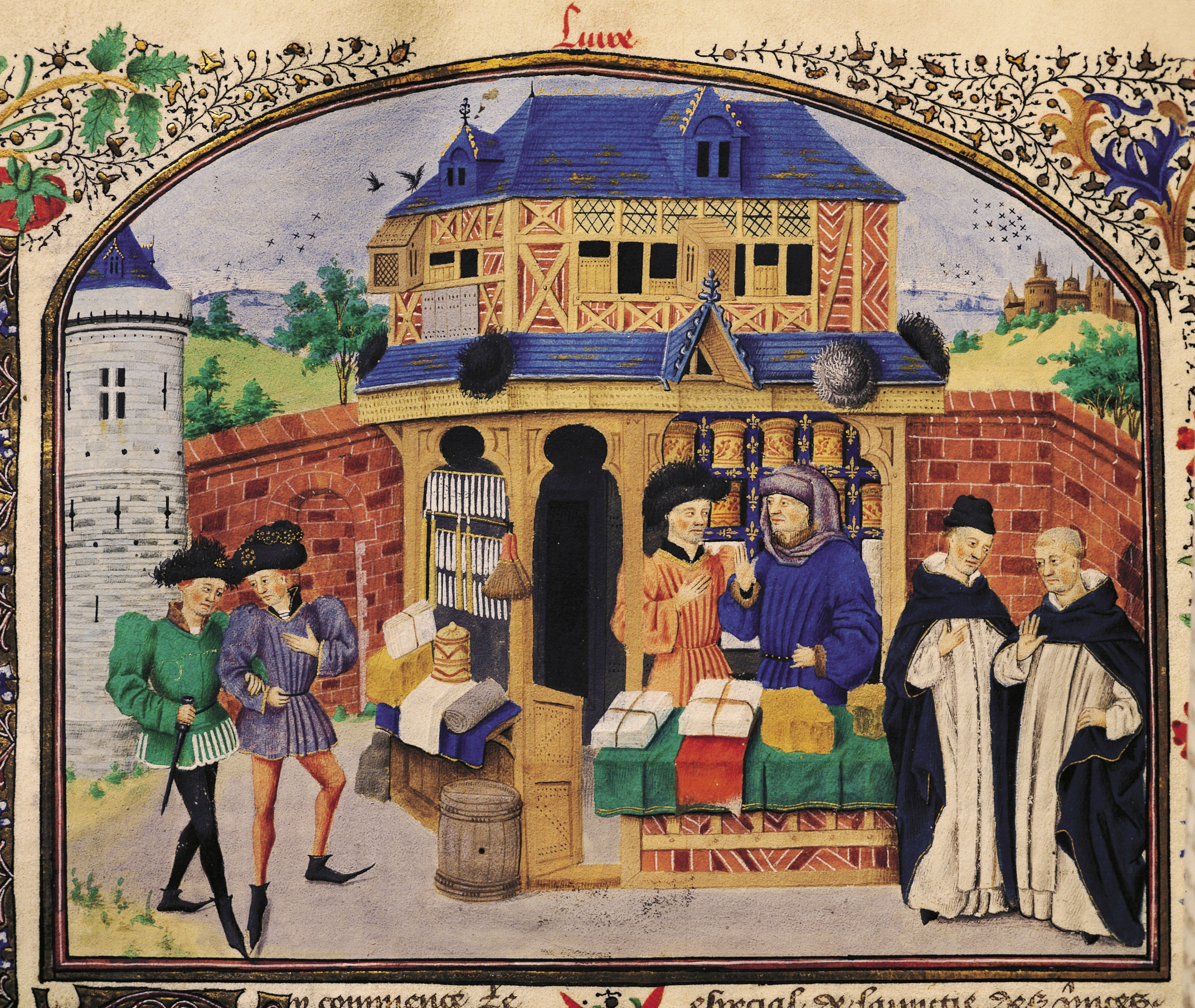

The three species of friendship, miniature from Ethics, Politics, Economy, by Aristotle, manuscript, folio 127 verso, France, 15th Century © Photo: Scala, Florence / Bibliothèque Municipale, Rouen

Share article